V. Five principles of an internationalist just transition to overcome the traps of the ‘green’ economy

The global debate on sustainability is being shaped by the powerful interests and trade agendas of already-industrialised nations. As a consequence, so-called ‘green’ policies are rarely motivated by environmental protection as much as by environmental protectionism. This prompts critical questions about who defines what is ‘green’, and for whose benefit. In a global context of environmental regulations increasingly serving as covert barriers to trade, perpetuating inequalities and geopolitical tensions, an internationalist framework for a truly just transition has never been so important.1Breno Bringel and Sabrina Fernandes, ‘Towards a New Eco-Territorial Internationalism’, in The Geopolitics of Green Colonialism (London: Pluto Press, 2024).

It is strategic to reclaim the narrative on sustainability, and to promote a just transition framework that defends the interests of the Global South, in ways that can guide policy and action today, while building conditions for more robust action in the future. To leave no country behind, policy must address issues in multilateral governance, climate financing, global trade and carbon pricing, green innovation and technological transfer, and, of course, pathways for coordination that ensure different countries and regions can work in cooperation.

Inequalities in the transition and sustainability agenda and the rise of green protectionism

There are various sets of inequalities around the sustainability agenda, including: (i) inequalities of power in terms of agenda-setting; (ii) financing inequalities in terms of access to investment for the energy transition; (iii) trade/technological inequalities that reproduce an international division of labour that condemns developing nations to underdevelopment; (iv) and inequalities within nations, which are exacerbated when countries pursue green transition plans in the form of handouts to large corporations at the expense of labour. A full review of these different forms of inequality is beyond the scope of this article, but I will try to flesh out some of the important implications for a just transition.

In many ways, the global sustainability agenda is dominated by a form of carbon obsession. This ‘carbon tunnel vision’ reflects Western countries’ sense of responsibility for climate change mitigation, while often overlooking other critical aspects of sustainability that also have implications for economic transformation.2Chang, H. J., Lebdioui, A., & Albertone, B. (2024). Decarbonised, Dematerialised, and Developmental: Towards a New Framework for Sustainable Industrialisation. UNCTAD; Estevez, I., and J. Schollmeyer. 2023. ‘Problem Analysis for Green Industrial Policy’. Toward AI-Aided Invention and Innovation. Springer Nature. A narrow focus on carbon-footprint reduction, which will actually extract more resources from our planet, is incompatible with a broader view of ecological sustainability. The attempt to solve carbon emissions without reference to a socioecological perspective may generate higher material pollution and biodiversity loss while in effect worsening multiple crises. This can be observed in the case of green hydrogen, which presents considerable trade-offs in terms of ecological impacts, and the new forms of climate colonialism. This is why reclaiming the narrative on sustainability in a way that encompasses the various ecological issues that hinder human wellbeing across the world is a critical step towards a just transition at the international level (see principle 1).

There are also various economic inequalities that need to be addressed today, including on the financing front, even though their root causes are systemic and harder to tackle. It is obvious that clean energy technologies can help reduce the access gap for communities suffering from energy poverty. According to the International Energy Agency, in Africa close to 600 million people were without access to electricity in 2018. This situation reinforces existing socioeconomic inequalities and impedes the widening of access to basic health services, education, and modern machinery and technology. In Latin America, businesses suffer 2.8 electrical outages on average per month, and nearly 40% of firms have identified the power sector as a major constraint on their potential, according to the World Bank. As is usually the case, power outages also tend to exacerbate inequalities, as low-income households tend to experience more blackouts and power surges than high-income households. However, despite clear needs and the potential for low-cost clean energy production due to its significant cost advantages in labour, land, and construction, those regions are not the main recipients of investments in renewable energies. As shown in Figure 1, even though 2021 was a record year for global renewable energy investment (with around US$420 billion invested), renewable energy investment was below US$1 per capita in sub-Saharan Africa, while over US$100 in the USA, Canada, Japan, China, and the EU. Indeed, developing countries must often pay more for renewable energy projects than countries in Europe and North America. In Africa, for instance, the cost of capital for renewable energy projects is even higher than for fossil-fuel investments, which implies that the continent may miss out on an additional 35% of green electricity production under a 2 °C transition pathway. This of course leads low-income countries down carbon-intensive economic pathways, while constraining their ability to seize some of the ‘green windows of opportunity’.3Lema, R., Fu, X., & Rabellotti, R. (2020). Green windows of opportunity: Latecomer development in the age of transformation toward sustainability. Industrial and Corporate Change, 29(5), 1193–1209.

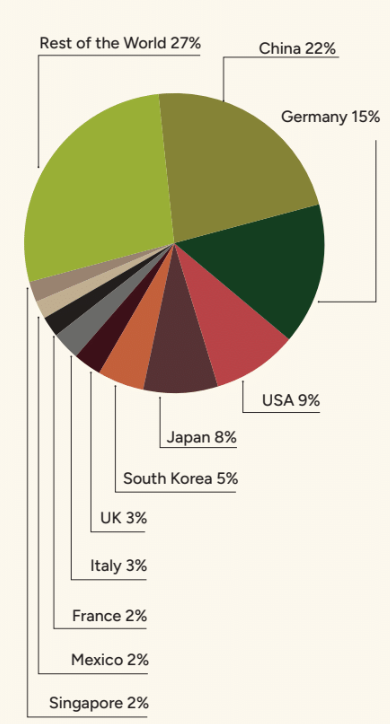

The expansion of low-carbon technologies generates opportunities for industrial development. But, so far, countries with a revealed comparative advantage in low-carbon technology products and environmental goods tend to be industrialised, high-income nations (especially in East Asia and the EU, as well as the USA). The trade of low-carbon technologies is also highly concentrated. Three countries (China, Germany, and the USA) account for almost half of all low-carbon technology exports (see Figure 2). Furthermore, most of the value-creation in renewable energy sectors has not occurred in low-income and/or fossil-fuel-dependent countries, where renewable energy jobs are arguably most needed to ensure a just transition. If the transition to a low-carbon economy enables industrial development in already-industrialised nations while renewing the limited role of most developing countries as sources of raw materials, this is likely to exacerbate economic disparities within countries and cast doubt on the central promise of the UN’s sustainable development goal of leaving no one behind.

As the global low-carbon economy grows, a radical policy shift is needed for developing countries to avoid being left or pushed behind. Proactive public policies (and industrial policies in particular), which influence land, energy, capital, and labour costs, could shape the geography of manufacturing supply chains for low-carbon technology. Indeed, most countries that have become large exporters of low-carbon technologies are not the most endowed in terms of land and energy resources, nor do they have the lowest labour costs; instead, they have proactively used industrial policies to develop the capabilities required to produce those goods. Those nations have also relied on forms of green protectionism, making it very difficult for developing nations to use the same policies to fight poverty as well as climate change.4Lebdioui, A. (2024) Survival of the Greenest: Economic Transformation in a Climate-conscious World. Elements in Development Economics, Cambridge University Press.

Instead of honouring their liabilities and responsibilities, the world’s major economies’ response to climate change has focused on securing a competitive advantage for domestic companies in capturing the industrial benefits that arise from their own decarbonisation efforts. The US government has been particularly explicit regarding its geostrategic interests in reducing China’s low-carbon technology dominance, and has therefore resorted to tariffs to protect its internal market from Chinese imports, but it is not alone in promoting green protectionism. Other governments have pursued green-protectionist policies in a more subtle way, often managing to circumvent trade rules by disguising their trade interests under the umbrella of climate action. For instance, the EU has also restricted the imports of goods that could enable it to meet its climate targets. A famous sticking point in the negotiations on the Environmental Goods Agreement (a multilateral effort within the WTO to liberalise tariffs on environmental goods) was the case of bicycles. While the Chinese government argued that a bicycle constitutes an environmental good, because it is an emissions-free form of transportation, the EU negotiators were reluctant to liberalise tariffs on bicycles for fear that a large influx of lower-cost, foreign-made bicycles would damage EU bicycle producers. The EGA negotiations have broken down as a result. More recently, concerns have been raised regarding the legality of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and its de facto role as an import constraint despite being framed as a climate-related action. The CBAM, which initially applies to imports of goods such as cement, iron, steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity, and hydrogen, could impose costs on developing-world exporters. In Africa, for example, it could cause a GDP loss of US$31 billion.

While green protectionism might seem like a reasonable attempt to safeguard domestic industries in their transition, the way ‘green’ industrial policies have been enacted by the world’s major economies fails to address the fundamental challenge of just transition: the response to climate change cannot be constrained by international borders, since the effects of climate change will not be. Through their green protectionism, rich nations are hurting everyone’s prospects of abiding by an emissions budget that can effectively keep us within the Paris Agreement targets.5Ghosh et al. even argue that the insufficient actions by rich countries are leading to a new form of climate imperialism. Ghosh, J., Chakraborty, S., & Das, D. (2023). El imperialismo climático en el siglo XXI. El trimestre económico, 90(357), 267–291.

Reclaiming policy space for green transformation internationally

When the poorest nations access pathways for economic transformation in a global framework for a just transition, all countries will stand to gain from climate-change mitigation and shared adaptative progress. Thus, rather than seeing global decarbonisation as an economic race, rich nations must recognise the value of inclusive green-industrial policies in developing nations, and actively support those efforts.

Here, I would like to outline five key practical guidelines, with concrete ideas compatible with the world’s political conditions today, that can help to build an internationalist just transition agenda that is beneficial to everyone.

1. Inclusiveness in the multilateral governance of the sustainability agenda

The current narrative on sustainability and how to fight climate change is dominated by a few rich nations, marginalising developing countries. This has harmed the credibility of global governance institutions, with some critics arguing for deep reform and others demanding their dismantling. In the meantime, rather than seeing change brought forth by these critiques, we are actually witnessing an increasing duplication of efforts and forums by rich countries, as governments vie to set (or impose) their own sustainability agendas.

Since the United Nations is still the preeminent global negotiating platform on climate and sustainability, it should be strengthened rather than reduced to just another among many venues.

For instance, the United States’ payments to the UN have been systematically partial and late, which heavily impacts the UN’s operations and ability to drive sustainability negotiations effectively. The UN should be strengthened with more funding, but also binding mechanisms to ensure compliance and prevent further unilateral and unconcerted efforts.

Meanwhile, multilateral processes (whether at COP or other UN platforms), also need to ensure equitable representation and participation in defining and implementing green policies. Too often, the ‘real’ climate negotiations take place before – and outside – the official negotiation table, excluding developing countries, whose endorsement is then sought after the fact. But it is difficult to ensure long term buy-in and full compliance without true consensus. A global coordination of sustainable finance taxonomies could also help ensure that the ‘environmental friendliness’ of projects is not determined by a handful of countries pursuing their own interests, but by norms and labels agreed upon by an international variety of stakeholders. Currently, the EU’s own sustainability standards are being pushed on other nations, notably leading to the stalled trade agreement with South American countries. This reflects the need for more universally agreed global baselines on sustainability. Given its complexity and social ramifications, such a process should not be driven by governments alone, but should also involve consultations with civil society, trade unions, and independent technical committees, as well as the private sector. It is also key to take the discussions on jobs, often siloed at the national level, to the international level. In many countries that heavily depend on fossil-fuel extraction as a source of jobs, global mobility and support for retraining will be essential in reducing popular resistance to low-carbon transitions. Global cooperation is especially needed in contexts where the skills gap between labour needs in areas of decreasing and increasing employment is too great; where workers are not willing to be relocated; and where fiscal constraints prevent the payments of benefits or employment subsidies for workers affected by low-carbon transitions.

Labour-market policies will be critical in avoiding potential labour misalignments over time, space, and across differing education levels. Policies that ensure that workers can adapt and transfer to new industries through the provision of upskilling services can be complex to design and implement. This is why the ILO can play a stronger role in supporting peer-to-peer learning and capability-building, emphasising retraining programmes, social safety nets, and inclusive economic development strategies that leave no one behind.

2. Developmental quality and purpose in climate financing

We need investment capital to flow to where it is most urgently needed and where it has the highest ecological and developmental spillovers. This would imply tripling investments for energy transition in Africa, for example, which currently represents a modest 2% of total renewable energy investments worldwide. According to UNECA estimates, the African continent needs at least US$190 billion a year for renewable energy financing (it currently receives US$60 million).

Rich nations have not kept their promise (made at the 2009 UN climate summit in Copenhagen) to channel US$100 billion per year to poor nations, beginning in 2020, to help them adapt to climate change and mitigate further rises in temperature. But beyond these missed targets, attention must also be drawn to the type of climate finance provision to date. Rather than supporting green economic transformation, most climate financing has consisted of non-concessional loans rather than grants, and focused on funding climate-mitigation initiatives over climate adaptation and resilience. One the key reasons that developing countries struggle to finance their own transition plans is because of their high debt levels and high costs of borrowing. As such, climate financing with developmental purpose should help reduce debt rather than create more of it. Loans add to debts of developing nations, tending to foreground expected capital returns rather than other social benefits in the evaluation of projects. (Principle 1 could help to coordinate frameworks for debt amortisation through domestic green investment.)

Considering their economic needs and different responsibilities in the context of the climate crisis, developing countries need significant financing not merely to import low-carbon technologies but to support local climate-resilient economic transformations. The specific approaches and priorities are matters of domestic sovereignty, and should not be dictated by rich nations using financial power. How exactly to fund the investments and grants for transformative green projects in the developing world thus becomes a key question. One option would be for rich nations to share some of the income earned from levying carbon taxes with the developing countries that pay them. Another way could be to repurpose excise taxes on fossil fuels, so that funds raised actually have a proper climate and development destination, while understanding that carbon taxation should follow a progressive approach in the first place, as further argued in the third principle here.

3. Bold pragmatism in reforming global trade rules and differentiation in carbon pricing

The current trade rules often disadvantage developing countries in their pursuit of green industrial policies. We need to push for reforms within international trade frameworks to accommodate the developmental needs of these countries. This also implies a different role for the WTO, which, rather than shying away from the global rise of industrial policies, could help facilitate the global discussion on the internationally and ecologically responsible use of green industrial policy and carbon taxation.6The WTO could also use the example of the Doha Ministerial Declaration on the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement and Public Health to expand TRIPS flexibilities for developing countries to access climate-related goods (including technology, as outlined in Principle 4). The WTO, along with its international partners, recently unveiled its assessment of global carbon pricing measures, but has failed to account for the principle of shared but differentiated responsibility.7WTO, IMF, UN, OECD, & World Bank (2024). Working together for better climate action. The International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations, The World Bank and the World Trade Organization. Indeed, an internationalist just transition also relies on moving beyond a universal price of carbon and towards differentiated carbon pricing that accounts for historic emissions.

Climate change is not caused only by existing carbon flows, but by the carbon stock already present in the atmosphere, which has been disproportionately produced by a handful of industrialised nations since the 19th century. To enable developing countries to continue developing, those countries must pay a premium for their continued emissions. As such, an incremental (or tiered) pricing of carbon (whereby newly emitted carbon would cost more than the previous ton emitted) would help to account for the principle of common but differentiated responsibility, providing poor nations some equity in time to plan for their transitions.

Incremental (or tiered) carbon pricing would be a far cry from the existing CBAM regime, which imposes unilaterally-assessed carbon pricing on the rest of the world. Achieving it will be no easy task, especially as estimations of historic carbon emissions are contentious. Again, Principle 1 will be critical in achieving a global consensus to pave the way.

4. Increased accessibility in green innovation through reorienting incentives towards greater technological diffusion and transfer

Developing nations need access to technology to enable both their climate resilience and their green economic transformations. To achieve this goal, low-carbon technology transfer needs to move from the status of charitable endeavour by the Global North to that of a pragmatic sustainability priority, whereby countries of the Global South are empowered to pursue maximal technology learning on their own terms.

This support for technology transfer can take various forms, such as technical and financial assistance for green productive capabilities, or further commitment to low-carbon technology transfer (at the core of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), especially by increasing support to institutions such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which, since its inception in 1991, has been financing the transfer of climate-related and other environmentally sound technologies to developing countries.8Technology transfer can be referred to as ‘a broad set of processes covering the flows of know-how, experience and equipment for mitigating and adapting to climate change amongst different stakeholders such as governments, private sector entities, financial institutions, non-governmental organizations and research/education institutions’ (IPCC, 2000). This agenda could also be supported by the creation of a new fund, under the UNFCCC and GEF, to remove the first-mover disadvantage in areas (especially long-cycle technologies) where innovation is critical but risky and unlikely to attract private investors (e.g. energy storage).

Using the model of Fundación Chile, such a fund could then make research and innovation publicly available and open-source, to encourage followers and technological diffusion. This might require changing the incentives for open-source innovation for environmental technologies, so that innovators do not have to rely on restrictive intellectual property rights as a form of rent-generation. From a purely monetary perspective, this could be achieved with prize incentives, whereby innovators receive an initial payment instead of holding intellectual property rights. Another possibility would be limiting the length of intellectual property rights for technology that contributes to planetary health.

International agreements should also further encourage cooperation with – and the accountability of – the private sector, to support low-carbon technology transfer and cooperation in innovation for developing countries. This responsibility can be added to the mandate of the United Nations Global Compact, a non-binding initiative to encourage businesses worldwide to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies, and to report on their implementation.

It must be stressed that the above measures should not be considered a handout to developing nations. If we are to fight climate change successfully, developing countries (which represent 99% of projected global population growth, but have much lower responsibility for mitigating climate change) will need serious incentives to embark on more ecologically sustainable pathways.

5. Solidarity and cooperation in policy coordination at the regional and sub-regional levels

In light of the exclusionary nature of influential forums, as well as broader geopolitical realignments, developing nations need to build collective power in order to include themselves fairly within a common vision of green transformation. We need greater regional and South-South cooperation to identify common challenges, to find a unified voice in international forums, and to coordinate efforts to ensure the economic viability and resilience of renewable energy projects, which require economies of scale, complementary assets, and cross-border energy integration and transmission to allow for intermittency.

In small economies, where the domestic market demand is often not large enough to reach economies of scale, green economic transformation requires access to another country’s larger market demand and also multilateral coordination towards regional developmental goals. In regions like Africa, the Caribbean, and Central and South America, where individual markets may be limited (with the prominent exception of Brazil), regional integration is critical to ensure the coordination and perenniality of demand-side policies, and to build regional value chains that can foster industrial transformation, especially for small economies. Neighbouring countries must leverage their complementary assets (whether that is critical minerals abundance, manufacturing capacity, renewable energy potential, proximity to important trade routes, etc) to develop an efficient regional industrial ecosystem around climate-related technologies. This requires us to move beyond the linear approach of trade liberalisation, and focus instead on ‘developmental regional integration’,9 Ismail, F. (2018) ‘A Developmental Regionalism Approach to the AfCFTA’. TIPS Working Paper.

which emphasises macro- and micro-coordination in a multi-sectoral programme embracing production, infrastructure, and trade.

Developmental regional integration mechanisms span a wide spectrum: from knowledge-sharing on critical material supplies and region-wide certification for low-carbon products, to pooling limited R&D resources for joint innovation and shared challenges (such as high-altitude mining in the Andean region, or developing solar plant equipment that is resilient to the Sahara’s extreme temperatures).

In practice, there are many challenges to green regional development: political and ideological differences, external influences, gaps in physical infrastructure connectivity, as well as disparities in economic development between neighbouring countries, can all generate resistance to integration. Despite these challenges, many regions around the world have successfully pursued various levels of integration (such as the European Union, ASEAN, and the African Union, among others), which can serve as guides. For instance, an important step towards regional integration in Africa has been taken with the signing of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement in March 2018. The agenda of developmental green integration remains full of challenges – but also of opportunities – for some of the world’s poorest regions.

As countries take part in the green industrialisation race, and vie for influence in the international convening spaces focused on sustainability, there are great risks of reproducing existing patterns of inequality, both within and among nations. This is why this article aimed to reflect what can be done under current political and economic conditions to advance a more internationalist just transition agenda, avoiding the developmental and ecological traps that are arising in the global ‘green’ economy. A socially inclusive, truly just transition at the global level cannot be achieved through policy alone: it will require an unprecedented level of political dedication at local, national, and global levels. But nor can the just transition be achieved without expanding policy space for green economic transformation in developing nations. A pragmatic approach to the just transition requires revisiting various policy domains, across trade, financing, intellectual property rights, environmental technology, carbon pricing, labour markets, and the multilateral governance mechanisms that underpin them. It requires policy reforms that look beyond short-term interests, adopting a long-term horizon – but which need to be developed and enacted immediately. It is by combining urgency with total commitment to the long game that we can really begin to set the conditions for a new era of prosperity for both current and future generations, on both sides of the equator.

___

This article is part of the Energy Transition dossier to be launched in March 2025.

FOOTNOTES

- 1Breno Bringel and Sabrina Fernandes, ‘Towards a New Eco-Territorial Internationalism’, in The Geopolitics of Green Colonialism (London: Pluto Press, 2024).

- 2Chang, H. J., Lebdioui, A., & Albertone, B. (2024). Decarbonised, Dematerialised, and Developmental: Towards a New Framework for Sustainable Industrialisation. UNCTAD; Estevez, I., and J. Schollmeyer. 2023. ‘Problem Analysis for Green Industrial Policy’. Toward AI-Aided Invention and Innovation. Springer Nature.

- 3Lema, R., Fu, X., & Rabellotti, R. (2020). Green windows of opportunity: Latecomer development in the age of transformation toward sustainability. Industrial and Corporate Change, 29(5), 1193–1209.

- 4Lebdioui, A. (2024) Survival of the Greenest: Economic Transformation in a Climate-conscious World. Elements in Development Economics, Cambridge University Press.

- 5Ghosh et al. even argue that the insufficient actions by rich countries are leading to a new form of climate imperialism. Ghosh, J., Chakraborty, S., & Das, D. (2023). El imperialismo climático en el siglo XXI. El trimestre económico, 90(357), 267–291.

- 6The WTO could also use the example of the Doha Ministerial Declaration on the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement and Public Health to expand TRIPS flexibilities for developing countries to access climate-related goods (including technology, as outlined in Principle 4).

- 7WTO, IMF, UN, OECD, & World Bank (2024). Working together for better climate action. The International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations, The World Bank and the World Trade Organization.

- 8Technology transfer can be referred to as ‘a broad set of processes covering the flows of know-how, experience and equipment for mitigating and adapting to climate change amongst different stakeholders such as governments, private sector entities, financial institutions, non-governmental organizations and research/education institutions’ (IPCC, 2000).

- 9Ismail, F. (2018) ‘A Developmental Regionalism Approach to the AfCFTA’. TIPS Working Paper.

RELATED ARTICLES

Does the ‘Military-Digital Complex’ Control Everything?

Who are the humanitarians?

Why Digital Sovereignty Matters

A Lawless Trump Administration Runs Amok in the Caribbean

A post-social question

The Politics of Normality in Wartime Russia and Ukraine

On the Limits of Humanitarianism

The Humanitarian Machine: Waste Management in Imperial Wars

Discord by design: The deliberate precarity of Syrian labourers in Lebanon

Displacements

Reclaiming Digital Sovereignty: A roadmap to build a digital stack for people and the planet

Labour, Foreign Aid, and the End of Illusion

The Peasant’s Arrested Revolution

Western Humanitarianism: Saving Lives or Regulating Death?

Non-Aligned approaches to humanitarianism? Yugoslav interventions in the international Red Cross movement in the 1970s

I. Introduction: Containing politics dossier

III. Energy and ecosocial democracy against fossil gattopardismo